Lockdown Times: A Temporal Perspective to ‘Stay Home Stay Safe’

- By Vikas Prabhu --

- june 23, 2020

Temporal perspective, Clock-time, Circadian rhythm, Psychological time

If no one asks me, I know; if I wish to explain to him who asks, I know not. – St. Augustine (on time)

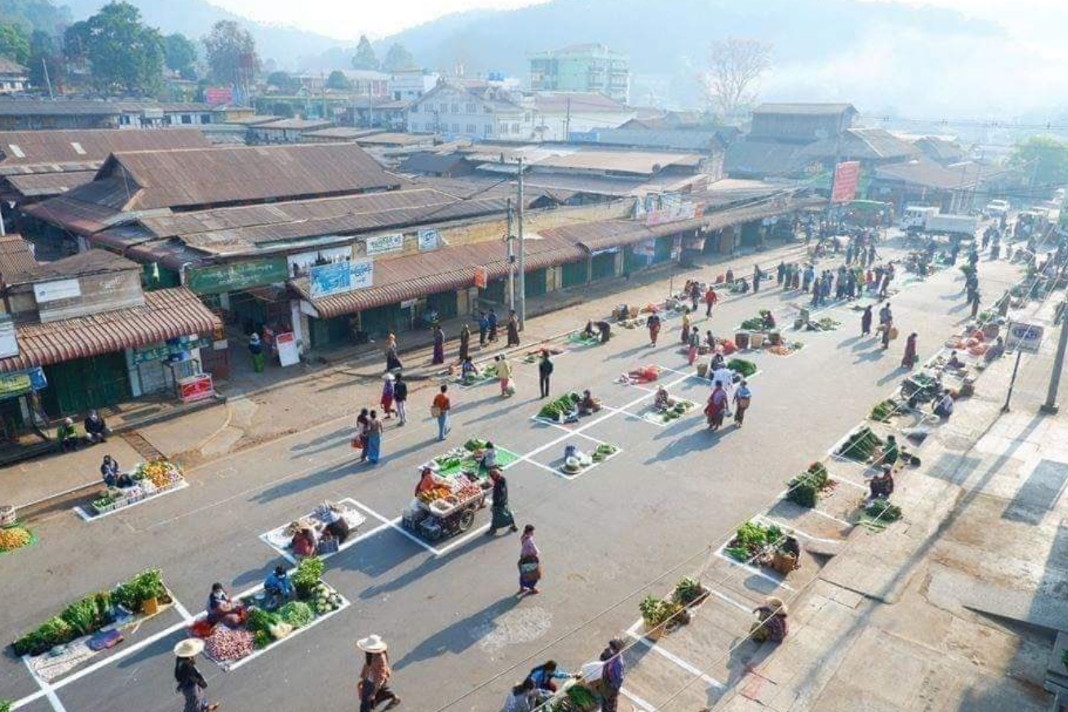

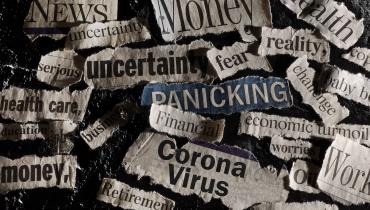

In the backdrop of the COVID-19 pandemic lockdown, the message ‘Stay Home, Stay Safe’ resounded across the globe. However, as lockdowns entered a prolonged period, staying home seemed to evoke dismay amongst the masses as, apart from pathologies such as anxiety, stress, and boredom, individuals and families witnessed a gradual disruption in the daily routines. This impacted individuals’ timeliness concerning their daily schedules and sleep-waking cycles (See here, here, here, and here). In response, authorities suggested that families proactively incorporate a daily routine consisting of a fixed set of tasks that can render a sense of normalcy in the lockdown period. In this article, I suggest that a plurality of temporal perspectives undergirds our daily lives and, on that basis, challenge the prescription of “planning a fixed daily routine” as myopic.

The temporal perspectives of daily life

In the opening sequence of Jamie Uys’ 1980 classic, The Gods Must Be Crazy, the narrator contrasts the hectic punctuality-driven daily schedules of Johannesburg dwellers with the leisurely paced days of the Kalahari bushmen. This anecdote, in my opinion, clearly emphasizes the aspect of temporal perspectives. While the urban denizen espoused a ‘clock-time perspective’ where the day is divided into specific units to be judiciously planned and organized, the tribesmen seem to be driven by ‘event-time perspective’ where action is contingent upon occurrences such as biological needs, diurnal/seasonal changes. The bushmen’s leisurely temporal perspective may be an endowment of the relatively calm environs of the deep Kalahari that is not characterized by the frantic zeal of a cityscape.

To clarify the concept of temporal perspective, let me invoke some history on our understanding of the nature of time. Aristotle regarded time as a measure of movement, whereas the medieval Christian Saint Augustine (an ardent Aristotelian) felt that time was a confounding concept. Post renaissance, while some scholars (e.g., George Herbert Mead, Jean Piaget) stressed on time as a socialized construct, others (e.g., Immanuel Kant, Henri Bergson) contended that time was a concept underlying our consciousness. Bertrand Russell seemed to blend the diverging perspectives when he suggested that time has two modes of perception: (1) relations of succession or simultaneity between objects in the real world, leading to a perception of “before, after, or together,” and (2) memory-based association between the perceiving subject and the objects, leading to conceptions of “past, present, and future.” (Russell, 1915). Thus, while objective mode facilitated the perception of change, subjective mode provided conception of continuity to it. Hence, in the flux of an interplay between perception and conception of time, we fathomed our conscious experiences (Schütz, 1967), and, hence, “constructed” an image of ongoing reality situated in the extended platform of the present moment (James, 1890). In summary, scholars suggested that time was like a fabric that brought together the components of reality in flux and facilitated its weaving into narratives.

Building on the above perspective, sociologists suggested a dual notion of time: time as ‘standard time,’ which was intersubjectively determined, like, for instance, socially accepted calendars; and time as ‘inner time’ which was a conscious inner flow founded upon “the psychological rhythms of the organism” (Berger & Luckmann, 1966, p. 40). This dualism of subjective and intersubjective influences to the experience of time can be said to foster variety in individuals’ temporal perspectives. Thus, though all of us receive the same astronomically-determined units of 24-hours in a day, each of us manifests a different lived experience of daily life in accordance with our temporal perspectives.

Towards a broader temporal discipline

Research has shown that a roughly 24-hour biological cycle – the “Circadian Rhythm” –underlies our metabolic processes. Scholars (e.g., Aschoff, 1965) have observed that various mishaps – such as disorientation in sleep-waking cycles – occur when the biological cycle is desynchronized from the Circadian rhythm. Hence, maintaining a fixed routine of activities in sync with the 24-hour cycle can facilitate the healthy functioning of the body. This is the basis on which many experts prescribe the maintenance of daily timetables. This prescription, however, takes a narrow perspective as it neglects the aspect of psychological time. Scholars have observed that psychological time moderates individuals’ evaluation of the effectiveness of their activities, which can significantly influence their levels of creative engagement (Zimbardo & Boyd, 2008). Hence, incorporating a temporal discipline that accounts for psychological time seems imperative if one aspires to elevate one’s daily functioning from “mechanical involvement” to “creative engagement.”

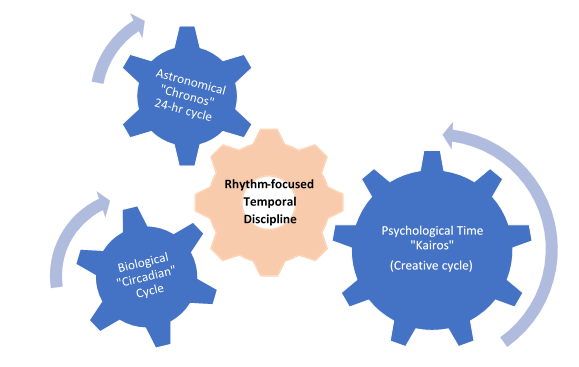

Concerning the above, I emphasize the need for a broader and dynamic perspective to temporal discipline that, inter alia, accounts for two things: (1) plurality of temporal perspectives that undergird our daily lives, and (2) an exercise in harmonizing and not merely synchronizing. I illustrate this idea of broader temporal discipline using the notion of interspersed gears in the below figure. As can be seen, a broad temporal discipline acknowledges multiple underlying cycles and attempts to find a common rhythm that strikes mutual alignment between them.

The above conception does not reject the need for daily timetables; instead, it emphasizes that a dynamic perspective to creating and enacting timetables is needed. Hence, while maintaining a static or fixed schedule for everyday activities may keep one occupied, a timetable that does not account for changing subjective and intersubjective contexts – i.e., evolving psychological time perspective – on an ongoing basis, may lead to gradual disorientation in psychological engagement. That may explain the emerging reports of pathological effects over time, as indicated at the beginning of this article.

Lockdown times have endowed increased temporal agency upon us, i.e., individuals have relatively more control over planning and executing their daily schedules. I suggest that we exploit this opportunity to recognize the rhythms of our creative selves and integrate it into our daily lives, which spiritual masters have long emphasized as harmony between mind and the body. With corporates looking to plan permanent work-from-home arrangements, broad temporal discipline may just have to become the order of the day.

References

-

Aschoff, Jürgen. (1965). Circadian rhythms in man. Nature 148(3676): 1427-1432.

-

Berger, Peter & Luckmann, Thomas. (1966). The Social Construction of Reality. London: Penguin Press.

-

James, William. (1890). The Principles of Psychology. NY: Henry Holt.

-

Russell, Bertrand. (1915). On the experience of time. The Monist 25(2): 212-233.

-

Schütz, Alfred. (1967). The Phenomenology of the Social World. Evanston, IL: Northwestern Univ. Press.

-

Zimbardo, Philip & Boyd, John. (2008). The Time Paradox: The New Psychology of Time That Will Change Your Life. NY: Free Press.

Vikas Prabhu