Peripheral Vision: A View of the Pandemic from the Periphery of Society

- By Anupama Kondayya --

- July 27, 2020

Share This Story

Transgender, Diversity, Social Change, Pandemic

In the Indian epic Ramayana, when Rama was leaving for exile, the people of Ayodhya started following him. At the banks of the river Sarayu, he asked the men and women to return to Ayodhya. Fourteen years later, when returning from exile, Rama found some people still waiting by the river. Rama had asked only men and women to return. But those waiting were neither men nor women, they belonged to the third gender. So, they had stayed in the same spot waiting for his return. Rama was touched by this gesture and conferred upon the third gender the power to bless others.

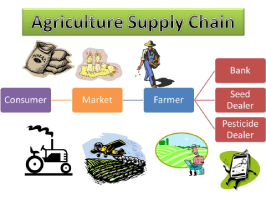

This is one of the many myths associated with the transgender community in India, especially the hijra community, which is a highly institutionalized, self-contained community living on the periphery of Indian society. From being acknowledged and well-integrated into Indian society in the pre-colonial times, with rulers across religions patronizing them, the community came to be criminalized and marginalized during the colonial rule with the passage of the Criminal Tribes’ Act of 1871, which targeted the hijras and stated that their being seen in female clothing in public or performing publicly may attract arrest without warrant. However, the process of initiation into the community involves renouncing worldly life not unlike monks, and taking up female clothing and behaviour. As a result, the institutionalized transgender community lives in closely clustered neighbourhoods today. Renunciation implies that they can only survive on the charity of others, leaving only two formal sources of income for the community - begging (mangti) and congratulatory appearances (badhaai) at weddings and childbirth to confer blessings in exchange for money. Due to community living and obligation to share earnings with their gurus, individuals may engage in prostitution outside formal community rules to supplement income.

Having left their families or being abandoned, individuals often do not possess any formal documents or even birth certificates to Help secure documents such as ration cards, voter IDs or Aadhaar cards. This positions the community outside the social security net, leaving them to procure essentials such as groceries from neighbourhood vendors, often on credit that is settled when there is income. The lack of documentation also means the inability to open bank accounts. Evidently, there are many hurdles in the way of community members becoming documented and integrated citizens of India.

In recent years, there have been steps towards integrating the community, with state-level transgender welfare boards, recruitment initiatives, the case of National Legal Services Authority of India (NALSA) Vs. Union of India leading to the official recognition of the third gender in India, as also the Transgender Persons (Protection of Rights) Act, 2019 prohibiting discrimination against transgender individuals in education, employment, housing and healthcare. But how has this played out on the ground especially in view of the pandemic?

The systemic exclusion of the transgender community has only been magnified during the pandemic. Recurring lockdowns, enforcement of physical distancing, prohibition on large celebratory gatherings have made it impossible to beg, earn badhaai or engage in prostitution. The community is cash strapped with the money running out early. Some members have faced evictions due to lack of money to pay rent. With neighbourhood stores closed, hoarding behaviour during lockdowns, and lack of income, access to essential supplies has been challenging. The lack of any form of identification and bank accounts means being left out of the list of beneficiaries for state relief, and not being able to receive state support through direct deposits.

This situation has far reaching effects on the well-being of community members. Many community members may be in the process of gender reassignment involving hormone injections which need to be administered regularly. The community is susceptible to HIV-AIDS as well, and members may be receiving anti-retroviral therapy (ART) for the same. Discontinuity in the therapy may lead to developing resistance and make the therapy ineffective. This is a serious threat with availability of medicines being affected during the pandemic. Individuals also need to consume enough and healthy food while undergoing these therapies to make them effective, which is challenging given the lack of supplies. These factors as well as increased susceptibility to infection due to surgeries or health conditions lead to adverse health outcomes for the community.

The situation of the transgender community forces one to think about structural and systemic factors that lead to exclusion and invisibility. Clearly, policies and legislation alone may not be enough to make an impact on the ground. According to Scott (2013), institutions are supported by all three of regulative (rules), normative (expectations) and cognitive (beliefs) aspects. Unless the normative and cognitive aspects are aligned with the regulative ones, lasting change may not occur. To the extent that gender has been seen as an institution (McCarthy & Moon, 2018), gender regimes may be disrupted only when change occurs at the macro level (policies/laws) as well as micro level (behaviour of individuals) to enable inclusion.

Thus, it is important to pay attention to change implementation such that regulations may percolate to the ground to impact the bureaucratic structure itself (adapting rules to unique problems of the community), the societal structure (norms) and the cognitive structure (beliefs) around the re-institutionalization of the third gender. The transgender community may be recognized separately on official forms, and yet be bereft of aid during the pandemic for the lack of other documentation which they may be unable to produce. An Act may prohibit discrimination against them matters of health and housing, and yet they may be evicted by landlords when money runs out during the pandemic, or discriminated against in health centres due to long held notions. Thus, change may need to be imagined as an hourglass model as shown in the figure, where the percolation results in a build-up of impact for the community through the alignment of new regulative, normative and cognitive aspects around the re-institution of the third gender through efforts from the ground up to diffuse the regulative aspects into society and its members.

Reference:

1. (Indian) Criminal Tribes’ Act, 1871

2. Kalra, G., & Shah, N. (2013). The cultural, psychiatric, and sexuality aspects of hijras in India. International Journal of Transgenderism, 14(4), 171-181.

3. McCarthy, L., & Moon, J. (2018). Disrupting the gender institution: Consciousness-raising in the cocoa value chain. Organization Studies, 39(9), 1153-1177.

4. Nanda, S. (1986). The Hijras of India: Cultural and individual dimensions of an institutionalized third gender role. Journal of Homosexuality, 11(3-4), 35-54.

5. Roscoe, W. (1996). Priests of the Goddess: gender transgression in ancient religion. History of Religions, 35(3), 195-230.

6. Scott, W. R. (2013). Crafting an Analytic Framework I: Three pillars of institutions. Institutions and Organizations. SAGE Publications, Inc, fourth edition edition.

Anupama Kondayya