Power Distance: An Indian Perspective

- By Ritu Tripathi and Uday Vijayan

- June 02, 2020

Power Distance , Safety, India

Power Distance

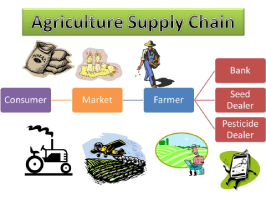

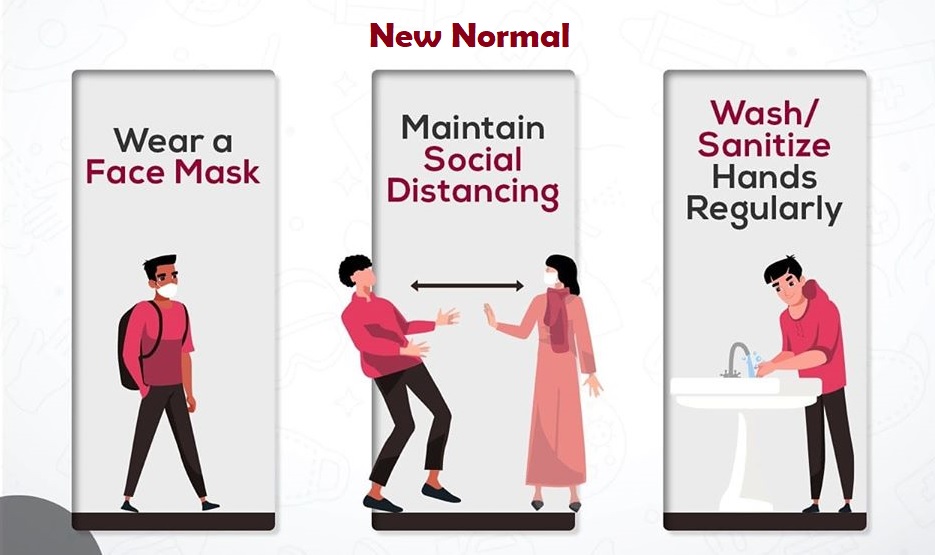

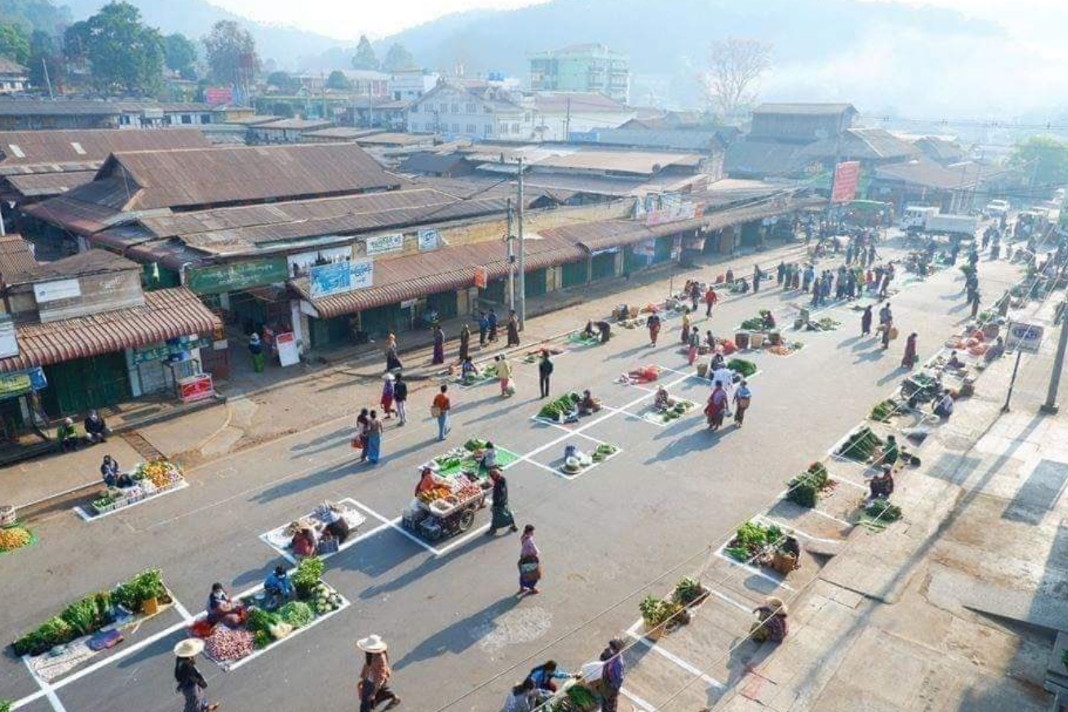

Power differential—be it in socio-economic status, professional and educational qualifications, jobs and occupations—is more acutely experienced in India than in many other countries around the world. The power distance index of India, 77, is much higher than the world average of 59. The key psychological aspect of power distance in India is that power dynamics are as much bottom up, as they are top-down, in that those low on power are at home with the power differential. This tendency makes us dependent on the diktats of trusted authority figures. In the realm of safety, it would imply that we would not proactively seek out information to engage in safety behaviours. We are better off being told what to do Hence, issuing very clear directives of ‘do’s’ and ‘don’ts’ in people-friendly, jargon-free manner is important. Of course, we all fall prey to fake news, precisely for this reason.

The bases of power are also important here. Although authority figures are perceived to wield an inordinate amount of power in high power distance countries, power does not always imply coercion or authoritarianism. What is unique about us Indians is that we are highly receptive to soft power, be it the charisma of leadership, opinions of experts, or the inherent respect for authority figures. Hence, meeting obligations and being responsive to the expectations of trusted others uniquely motivate us. RT’s own research suggests that Indians tend to be oriented more towards meeting obligations relative to enhancing individual autonomy. Unlike in the United States where citizens are protesting against the lockdown by framing it as the suppression of individual freedom, Indians, although obviously concerned with daily bread-and-butter issues, are not majorly framing it in that manner.

This means that safety appeals may work better when framed in a manner that accentuates soft power—the power of expertise, charisma, and trustworthiness, while invoking the obligations-orientation. Example: The statement “police needs your support” primes our Indian mindset to comply with the authority figure, while also arousing the motivations to oblige or respond to expectations. An important point to note is that because people are obligations-oriented or inherently trusting of authority figures, the responsibility of the powers that be, multiplies manifold. It would be the travesty of cultural values, if the trusted are not trustworthy enough, or if those low on power are exploited or taken advantage of.

Ritu Tripathi

Uday Vijayan