Rebuilding broken employment networks in India

- By Arnab Mukherji and Sankarshan Basu --

- july 06, 2020

COVID19, Migrant, Unemployment, Big Data

COVID19 induced lockdown of the economy has meant that individuals on daily wages became unemployed. With limited savings and no work, millions returned home – UP alone estimates receiving 32 million migrants. A natural question for them is, how will they find work again?

The Junta Curfew led nationwide lockdown from 25th March till 31st May 2020 has disrupted labour markets significantly. CMIE unemployment data shows India’s urban (rural) unemployment rate was 8.2% (6.1%) on the 15th of March 2020. By the 29th of March, the urban (rural) unemployment rate rose to 30% (21%). Further, CMIE data also shows that employment levels, between 390 – 410 million employees every month, crashed to 280 million in April 2020. While unemployment rates have begun returning to their pre-COVID19 levels there remain serious challenges for labour markets in India.

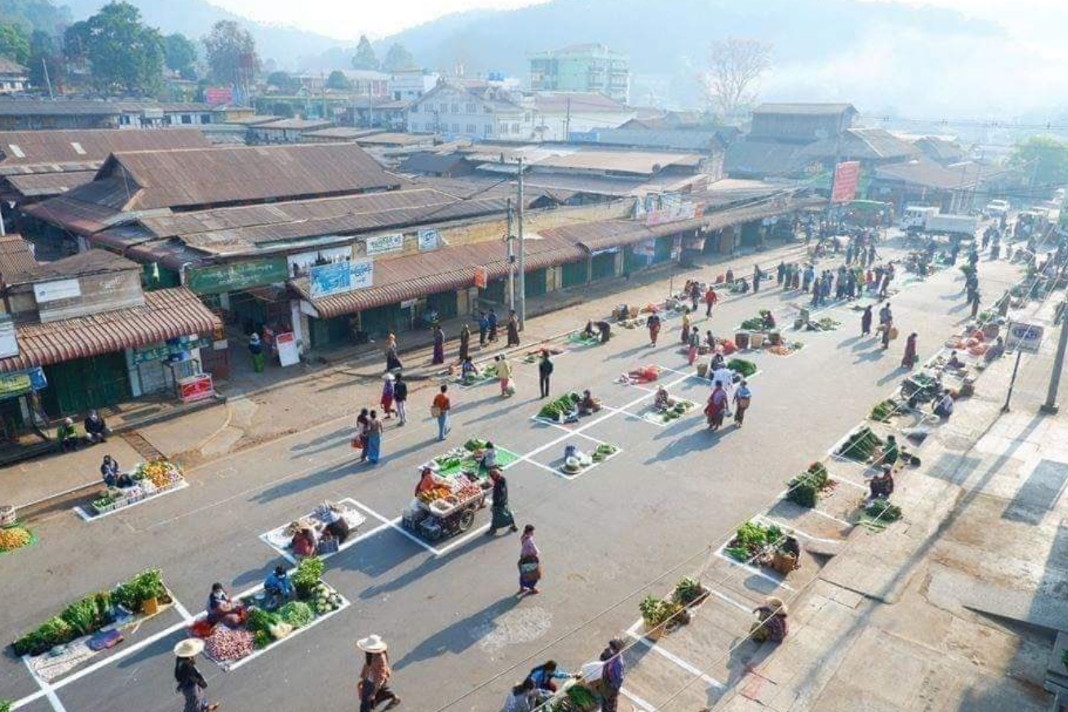

As unemployment levels have risen so has the demand for MGNREGA employment. Consider labour demand in a largely agrarian economy with some minor industries such as in Chittoor in Andhra Pradesh. MGNREGA data shows a sharp rise precisely as the nation enters lockdown reflecting an income crisis for households. In March 2020, aggregate demand for wage employment in Chittoor district stood at 2.2 Lakh days; subsequently, this rose to 3.2 Lakh days in April 2020, 4.1 Lakh days by May and rising to 4.5 Lakhs in June (by 20th June) 2020.

Source: CMIE

Source: https://www.nrega.nic.in/ (20th of June, 2020)

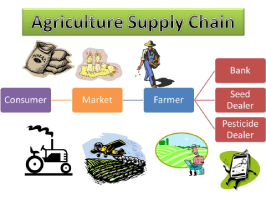

Looking closely at the lockdown’s impact on labour markets reveals a broken ecosystem for matching job seekers with employers, particularly migrants. Migrant labourers leave their states of domicile to be employed on informal contracts with low skills often working as coolies, carpenters, cooks, masons etc. During peak activity, the migrant labour’s presence was driven by various service providers, such as, the chai-wala, the panipuri-wala, and systems that would support their boarding and lodging; migration has also led to their symbiotically dependent ecosystems also collapsing.

Secondly, the separation of workers from employers generates two problems – an immediate loss of incomes has led to rising welfare needs in many labour surplus regions. With contracts being largely informal formal work separation norms cannot be claimed. Even standard social protection (e.g. PDS, MGNREGA, etc.) is available only if they return to their state of domicile. India’s identity as a union of states has led to a separation of welfare norms and state policies that is usually a good thing. With migration being a defining feature of India’s labour markets, state specific solutions that will emerge will miss efficiency gains in matching that can arise in a national job-matching platform.

Informal contracts create a second problem - loss of information about skills and worker productivity. Currently, in informal markets worker skills and productivity is recognized through on-the-job experience. A job loss does not retain this information in a transparent or verifiable manner for future employment. Both the employee and the employer must pay to discover this information in the future - the employer, by having to screen sub-optimal matches and the employee by being paid low wages.

With changing economic realities for the employer and a diminished availability of supporting ecosystem, a return to pre-COVID-19 employment is not obvious. The psychosocial disruption created by the harsh conditions under which forced return migration took place will inhibit many from returning to work. As will the uncertain regarding how long this pandemic lasts. For those who return, the absence of complementary ecosystems, will imply a higher cost of returning to work. A likely outcome is their absorption in local markets that have surplus jobs, but which were not financially attractive.

In a recent webinar hosted by IIM Bangalore, researchers, and government officers from labour deficit states (e.g. Gujarat) and labour surplus states (e.g. UP and Bihar) discussed ways to address this labour market crisis. While Gujarat’s experience is very different from that of Bihar or UP, these crises are jointly created! Thus, their response too must be sought within a common framework. Even as welfare programs continue to run on state-specific norms and there appears to be a strong case for state based labour exchanges. In addition, there is a case for a national platform for job listing, skill indexation, skill-matching, and efficiently managing job searches for both employers, and employees who are often located in different states.

Past attempts towards a national platform for labour has not engaged with the complexity of state specific challenges that are fundamental to the current challenge. We argue that a national IT platform that integrates each of the state specific apps or big data platforms is a critical need of the hour. This national resource could not only match job seekers to employers, but it can be designed to be internally consistent with governance norms of each state. Further, it can play an archival role by archiving the employment history of each worker and thereby create an institutional mechanism to retain skill discovery among labour. This could also enable the creation of skill-based efficiency wages and create skill segmented markets at different wages rather than a pooled labour market with low wages all around. Finally, such a framework may also allow the roll-out of state and union labour protection, and welfare schemes that can be transparently and identifiably linked to services that people need. As with all such things, the test of it depends on how well such a platform is implemented.

Arnab Mukherji

Sankarshan Basu