Unlocking Technology for Gig Workers

- By Rahul De’ and Deepti Sharma --

- june 23, 2020

Migrants, Gig Workers, ICT, Digital Divide, Seva Sindhu

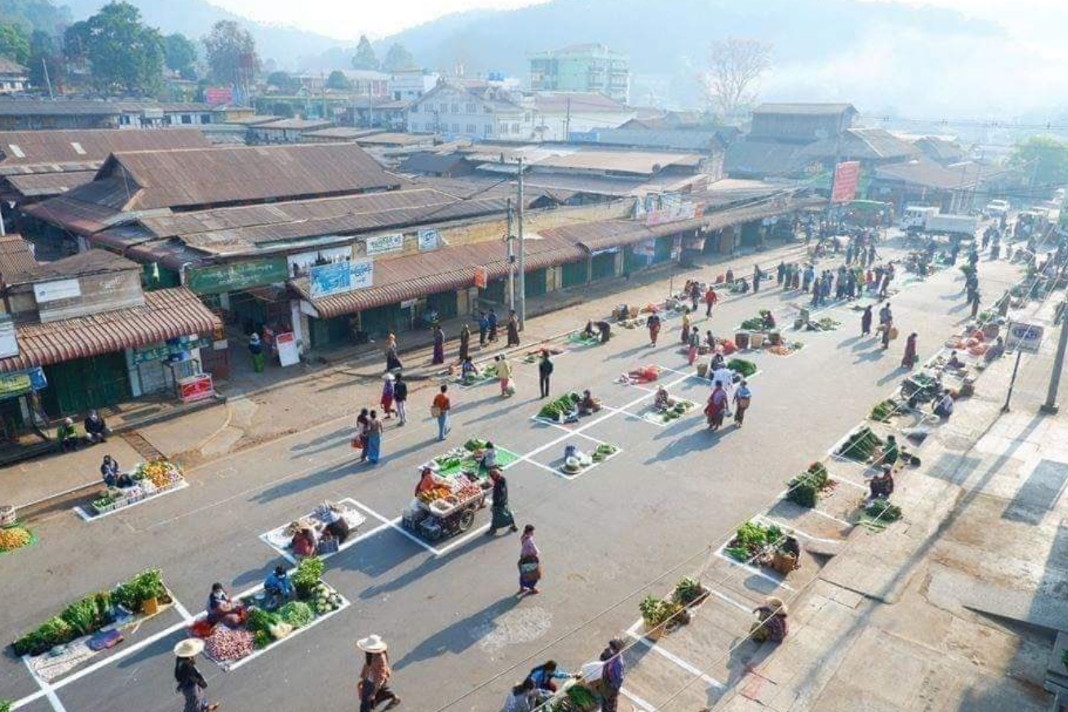

The enduring image of the pandemic lockdown in India was that of seeing lakhs of migrant workers trudging hundreds, sometimes thousands, of kilometres to go back home to their villages and homes. They did this against impossible circumstances – hostile police at state borders, no money with them as they were not paid wages for over a month, no food, little time to rest, mounting heat in late April and May in north India, and no hope that they will find food and medical attention in their home villages and towns. Their grit and determination were touching.

These migrants’ number 100 million and constitute the core of our labour class in all industrial towns and cities. As Chinmay Tumbe has pointed out in his book India Moving: A History of Migration, migration in India is a part of its history. Migrants have helped create the spatial shift in the economy, moving industrial activity to the heart of urban areas. Also, the prawasi (migrant) labour adapt and move from one sector to another, thus keeping the wheels of the economy moving.

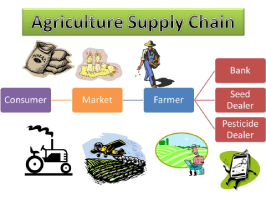

Migrant labour are the original “Gig” workers. They worked at skilled and unskilled jobs, often without firm contracts, through informal arrangements for pay, usually without any benefits, and often for piece-rate wages. They often work, if possible, at many jobs – stitch clothes in a factory during the day, and cook at several homes in the evening.

They are not very different from the modern Gig worker, those who have found employment through smart phone apps – the drivers for Ola and Uber, the delivery agents for Swiggy and Dunzo, and the skilled workers for Urban Clap. There are some differences though: the modern Gig workers are mainly in urban areas, and are usually not migrants but residents in these regions; also, the modern workers are on the right side of the digital divide with access to the internet and its facilities; and the modern workers are known and accounted for (mainly because of their use of smart phones).

Both groups, the old Gig workers and the modern ones, have suffered heavily during the lockdown in India. Gigs have disappeared, factories and establishments have closed, wages have not been paid, landlords have demanded and collected rent, and the government has given confused signals about their need to stay or return to home.

We envisage that the role of Gig workers, despite the hardships they have suffered in the lockdown, is likely to increase, not decrease even in the present period of unlocking of the economy. We think that all over the world, with the increase in digital work and work-from-home policies, the trend of independent, short-contract, piece-rate workers is going to increase.

We estimate that there are about 136 million informal workers in the economy in India, mainly working in urban areas, of which about 32 million are modern Gig workers, whereas the rest are part of the old economy, most of whom are migrants (FICCI, 2019).

What policies can improve the situation of both types of workers in the future in India? We have some recommendations which States can use for smooth transition of Gig workers during the unlock period:

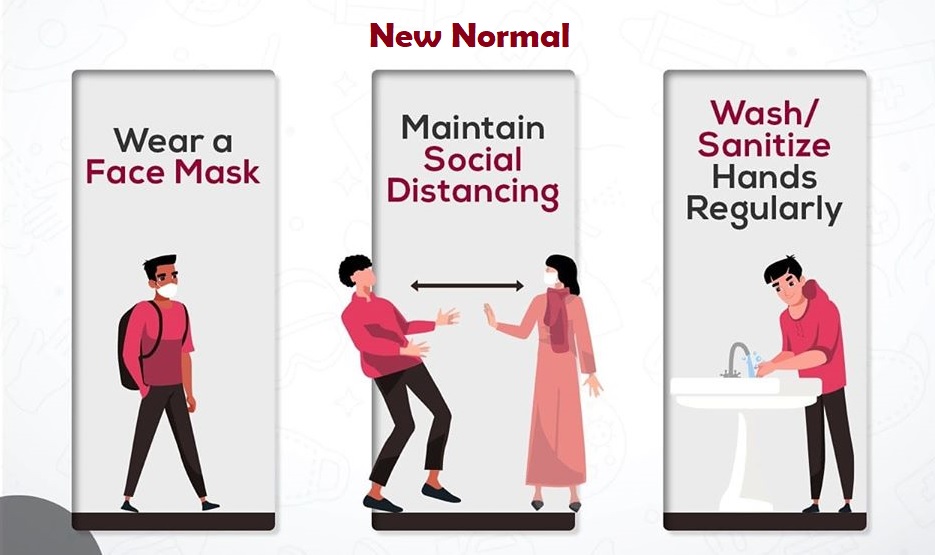

The government can introduce basic feature phone and smart phone apps that enable old economy Gig workers to be recognised and counted. The Seva Sindhu service being used by Karnataka government, to enable migrant workers to register to travel to their home state, is a good example. Though the Aadhaar card and number were meant to serve this purpose, they are better suited for smart phone apps than for feature phones. With a basic service (possibly enabled through dial-in USSD-like *# series), workers can request to be registered.

Such a phone-based service will help both old and new Gig economy workers – for registering as skilled or unskilled workers, for knowing the location in times of crisis, for enabling subsidy benefits (for instance, free foodgrains), for linking to potential employers.

Feature phone services can include cash transfers also. This is already available through UPI services. Cash transfers can be made to phone numbers by the government, and users can also make payments with these.

Most importantly, when Gig workers use phones and register themselves on government sites, they can be informed of government policies via text messages directly. Users of smart phones have benefited from messages on social media apps like Whatsapp, some of which is also fake news, but feature phone users who are from the old Gig economy have been left out. This correction would improve their chances of knowing their rights and the benefits available to them.

Overall, we feel that information and communication technology (ICT) devices, such as phones, can hugely benefit Gig economy workers. As their numbers increase in the post-pandemic situation, we hope governments and administrators will rely on ICT to reach out to them and assist them

References

FICCI, E. N. (2019). Future of Jobs in India 2022. Retrieved 2020, from http://ficci.in/spdocument/22951/FICCI-NASSCOM-EY-Report_Future-of-Jobs.pdf

Rahul De’

Deepti Sharma